In 1993, the Ann Arbor Observer published an in-depth feature article on the Ann Arbor High School Class of 1963. At the time, it was a nostalgic visit into the past on the thirtieth anniversary of graduation. Six classmates were interviewed and their memories and recollections painted a vivid picture of what it was like growing up in Ann Arbor. We are presenting the article here exactly as it was originally published twenty five years ago in 1993. We hope that you will find it to be an interesting and evocative trip down memory lane.

February 14, 1962,

Valentine’s Day, President John Kennedy announced that U.S. military advisers in Vietnam would return fire if fired upon. On October 1, James Meredith became the first black student at the University of Mississippi. On October 22, President Kennedy announced that the U.S. had detected a Soviet military buildup in Cuba—including the foundation for nuclear missile batteries—and ordered a blockade of the island. Later that fall, Rachel Carson published Silent Spring, the book since recognized as the beginning of the environmental movement.

On March 18, 1963, the Supreme Court guaranteed criminal defendants’ rights to counsel and banned illegally acquired evidence from state and federal courts. On June 17, the court ruled that reciting the Lord’s Prayer in public school was unconstitutional. Two months later, the civil rights movement grabbed the national spotlight with a March on Washington, where Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech.

The Academy Award for best picture of 1962 went to “Lawrence of Arabia.” Gregory Peck was named best ac-tor for “To Kill a Mockingbird” and Anne Bancroft best actress for “The Miracle Worker” Tony Bennett took home the best record Grammy for “1 Left My Heart in San Francisco.” Most popular on TV were Ed Sullivan, Lucille Ball, Dick Van Dyke, and “The Beverly Hillbillies” John Stein-beck won the Nobel Prize for literature, Linus Pauling the Peace Prize. The Tony Award for a musical in 1962 went to “How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying.”

In the fall of 1962, the New York Yankees defeated the San Francisco Giants in seven games to win the World Series. In January 1963, the Green Bay Packers beat the New York Giants for their second straight NFL championship. That spring, the Boston Celtics won their fifth straight NBA title. Sonny Liston was heavyweight champion of the world

In Ann Arbor in the fall of 1962 and the winter of 1963, Lyle Salamin was a senior at Ann Arbor High School, at Main and Stadium. He spent his waking hours either in class or at Arlan’s discount department store in Westgate, where he worked more than forty hours a week. On Saturday nights, his only free time, he’d head to the teen dances at the YMCA, the Argus building, or the Walled Lake Casino. To-day, thirty years later, he’s managing the Kiddie Land toy store in Farmington.

In Ann Arbor in the fall of 1962 and the winter of 1963, Lyle Salamin was a senior at Ann Arbor High School, at Main and Stadium. He spent his waking hours either in class or at Arlan’s discount department store in Westgate, where he worked more than forty hours a week. On Saturday nights, his only free time, he’d head to the teen dances at the YMCA, the Argus building, or the Walled Lake Casino. To-day, thirty years later, he’s managing the Kiddie Land toy store in Farmington.

Blondeen Munson, another member of the Ann Arbor High class of 1963, re-members the senior prom. She was on the planning committee—the theme was Bon Voyage—and she remembers the parties afterward, one at a classmate’s home that’s now the Kerrytown Concert House. Today, Munson works across the street from the concert house, at Legal Services of Southeastern Michigan.

Blondeen Munson, another member of the Ann Arbor High class of 1963, re-members the senior prom. She was on the planning committee—the theme was Bon Voyage—and she remembers the parties afterward, one at a classmate’s home that’s now the Kerrytown Concert House. Today, Munson works across the street from the concert house, at Legal Services of Southeastern Michigan.

The biggest moment in Chuck “Bird” Menefee‘s senior year came in the fall, when as quarterback he led Ann Arbor High to an undefeated season and the state football championship. He was named first team all-state. Now, “Charlie” Menefee runs a very popular new golf course—of his own design—between Harbor Springs and Petoskey.

The biggest moment in Chuck “Bird” Menefee‘s senior year came in the fall, when as quarterback he led Ann Arbor High to an undefeated season and the state football championship. He was named first team all-state. Now, “Charlie” Menefee runs a very popular new golf course—of his own design—between Harbor Springs and Petoskey.

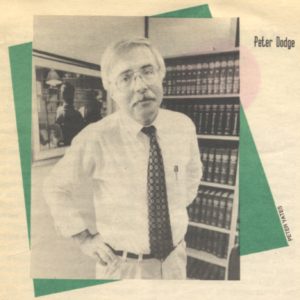

Peter Dodge remembers a football game that year, too, but for a different rea-son. A stabbing occurred, the first such incident in anyone’s memory. Dodge was one of the student council representatives who met with city council and managed to stave off a teen curfew that was discussed in the aftermath of the incident. Today, Dodge is a local attorney who does a great deal of pro bono work for the homeless and hungry.

Peter Dodge remembers a football game that year, too, but for a different rea-son. A stabbing occurred, the first such incident in anyone’s memory. Dodge was one of the student council representatives who met with city council and managed to stave off a teen curfew that was discussed in the aftermath of the incident. Today, Dodge is a local attorney who does a great deal of pro bono work for the homeless and hungry.

Neil Stehle was one of the more popular kids in the class of ’63. He’s pictured in the yearbook performing a handstand as a member of the gymnastics team. He was part of the Washington Club that visited New York City and Washington, D.C., over spring break. Five years after graduation, Stehle was killed in Vietnam.

Neil Stehle was one of the more popular kids in the class of ’63. He’s pictured in the yearbook performing a handstand as a member of the gymnastics team. He was part of the Washington Club that visited New York City and Washington, D.C., over spring break. Five years after graduation, Stehle was killed in Vietnam.

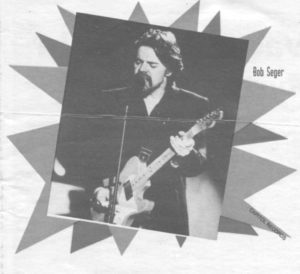

Robert Seger spent most of his free nights playing music at dances and in bars. He and his band, the Decibels, played a lot at the Schwaben Inn on Ashley, the Dandy Lyon in South Lyon, and at fraternities around campus. Now, Bob Seger can fill the Palace at Auburn Hills or Joe Louis Arena. His 1991 album, The Fire Inside,” sold more than a million copies.

Robert Seger spent most of his free nights playing music at dances and in bars. He and his band, the Decibels, played a lot at the Schwaben Inn on Ashley, the Dandy Lyon in South Lyon, and at fraternities around campus. Now, Bob Seger can fill the Palace at Auburn Hills or Joe Louis Arena. His 1991 album, The Fire Inside,” sold more than a million copies.

When the members of the Ann Arbor High School class of 1963 talk about their city back then, they remember it as a much smaller town. Ann Arbor had a population of 66.000 in 1960, about one third less than today. But there was only one public high school, so most of the city’s teenagers were in the same building at the same time every day. There were fewer elementary schools, and only three junior high schools: Slauson, Tappan, and Forsythe. A great many kids in the senior class had been going to school together since kindergarten.

Former city council member Larry Hahn, who graduated from Ann Arbor High in 1962, says Ann Arbor was also a far less transient town thirty years ago. “Most of the kids at Ann Arbor High had brothers and sisters in the grades around them,” he says. “So you knew your brother’s friends and your sister’s friends, or your friends’ brothers and sisters. Every-body knew everybody.”

Former city council member Larry Hahn, who graduated from Ann Arbor High in 1962, says Ann Arbor was also a far less transient town thirty years ago. “Most of the kids at Ann Arbor High had brothers and sisters in the grades around them,” he says. “So you knew your brother’s friends and your sister’s friends, or your friends’ brothers and sisters. Every-body knew everybody.”

That closeness was reflected in students’ pride in their school, says one member of the class of 1963. “We had a really strong focus on just being Ann Arbor High.”

Chuck Wilkins, who was senior class president in 1962-1963, remembers a school literally overflowing with kids. In his senior year, there were 2,460 students in tenth through twelfth grades, well over the number the school was designed to accommodate. “I can remember taking one class that actually met in a cloakroom,” he says. “Despite all that, though—or maybe because of it—we were a very tight group.”

Chuck Wilkins, who was senior class president in 1962-1963, remembers a school literally overflowing with kids. In his senior year, there were 2,460 students in tenth through twelfth grades, well over the number the school was designed to accommodate. “I can remember taking one class that actually met in a cloakroom,” he says. “Despite all that, though—or maybe because of it—we were a very tight group.”

The school fostered that pride from the very beginning. “One of the first things we did in tenth grade,” Wilkins says, “was that they played the school fight song over the PA system. We had to copy it down, punctuate it, and spell it, till we got it right.

“To this day, I still get a lump in my throat when I hear that song.”

Three decades later, such feelings remain strong. Nearly 400 people attended the last reunion of the class of ’63. For their thirtieth this July, a smaller but still sizable turnout is expected. Sandi Coleman—Sandi Ingram in high school—is on the planning committee. The twenty-fifth reunion, she says, was “three days of parties with everyone having a terrific time.” She talks to ex-classmates on the phone “all the time” and gets together with several frequently. She knows of one group of classmates that still vacations together every year.

Out of a class of 775, the reunion committee has recent addresses for 507. Thirty-three other class members arc known to have died, mostly from cancer or heart at-tacks. Of those who are alive, in touch, and still in Michigan, 167 are in Ann Arbor, eighty in Dexter, Saline, or other communities within a half-hour’s drive, and sixty-nine elsewhere in the state.

The other 140 class members live in twenty-six other states. There are twenty-nine in California and dozens more scattered along the West Coast and in Arizona. Fourteen live in Florida and several in Massachusetts and New York. Except for the Floridians, very few live in the Southeast—none are known to live in the Carolinas, Georgia, Arkansas, Mississippi, Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, Louisiana, Virginia, or West Virginia. One lives in Alaska, none in Hawaii. Just six members of the class have ad-dresses outside the United States—two in England and one each in Australia, Belgium, Denmark, and Israel.

Lyle Salamin

Lyle Salamin says the group he hung around with in high school was “the wilder crowd, more or less.” Their uniform, he remembers, was a black trench coat, pointy-toed shoes, and casino pants. “If you had a pair of shoes with toes so long that they curled up at the end, you knew you had yourself a pair,” he says. “The pants were skintight in the legs, with pegged cuffs so tight they had a slit on the side like a woman’s so you could get them off over your feet. They were too ‘hoody’ for Ann Arbor, so we had to get them at a place over in Ypsilanti.”

Lyle Salamin says the group he hung around with in high school was “the wilder crowd, more or less.” Their uniform, he remembers, was a black trench coat, pointy-toed shoes, and casino pants. “If you had a pair of shoes with toes so long that they curled up at the end, you knew you had yourself a pair,” he says. “The pants were skintight in the legs, with pegged cuffs so tight they had a slit on the side like a woman’s so you could get them off over your feet. They were too ‘hoody’ for Ann Arbor, so we had to get them at a place over in Ypsilanti.”

Salamin started working a few hours a week stocking shelves at Arlan’s when he was fourteen. At sixteen, with his father’s encouragement, he bought a brand-new metallic brown 1963 Chevrolet. “From that day on,” he says, “I was strapped. I had to work forty hours a week … at least forty hours a week.”

No matter how tight money was, though, he always went out on weekend nights, especially since he had a car. “Fridays, the Main Street store owners had dances in the parking lot on Main and William,” he remembers fondly. “The parents would drop their kids off at the dance and they’d go shopping.

“Saturdays, we’d go to the YMCA or Argus or else we’d sneak out of town, to the Walled Lake Casino or up to Houghton Lake. We had a curfew, but we’d always miss it and have to make up a story. Other guys would say their car broke down, but I had a new car, so I had

to be more creative. T-Town was big, too—Toledo.

“If you knew how to dance, you were cool. I can remember rushing home to watch ‘American Bandstand’ to see what the new dance craze was. Then everyone would have to learn it for the dances that weekend.”

On the few nights when there wasn’t a dance or a party to go to, there was always the Stadium strip. “We cruised all night, to Everett’s Drive-In, where they had California burgers, then to the A and W. I had to pop the hubcaps off the car ’cause it was so new everybody would think it was my daddy’s car. But nobody’s dad was go-ing to drive a car with no hubcaps.”

Sandi Ingram Coleman remembers cruising the strip, too. “It was right out of ‘American Graffiti,’ ” she says. “People would cruise the strip all night long, in kind of a figure eight. Even if you went to a dance, everyone would meet up at Everett’s later. You never went alone, al-ways with someone, and you had to pull into the space at the drive-in backwards.”

Sandi Ingram Coleman remembers cruising the strip, too. “It was right out of ‘American Graffiti,’ ” she says. “People would cruise the strip all night long, in kind of a figure eight. Even if you went to a dance, everyone would meet up at Everett’s later. You never went alone, al-ways with someone, and you had to pull into the space at the drive-in backwards.”

“Oh yeah,” says Salamin. “You had to pull in backwards so you could check out everybody else. If you didn’t back in, you were either from out of town or a geek.”

Other nights, the high school kids would head out to one of the drive-in movies—the Willow on Michigan Avenue, the Scio on Jackson Road, the Ypsi-Ann on Washtenaw and Golfside, or the University where Showcase is now. “We’d pack four or five people into the trunk, and one guy would drive in alone. If the person at the ticket stand asked him why he was alone, he’d say his girlfriend had to work,” Salamin laughs. After the movie, it was out to one of the gravel pits, where kids congregated, as if by magic, and “everyone would form a circle, all listening to the same radio station, usually CKLW. The next fall, I traded in my car for a Sixty-four Chevrolet Supersport with a reverberator under the dash that sounded like an echo chamber,” Salamin boasts.

When Salamin talks about “everyone,” he means everyone who shared his interest—girls, cars, dances. That was a large segment of the class. Chuck Wilkins, though, is quick to say that he “probably was a bit more serious than Lyle in my high school days.”

Wilkins’s foremost memory from high school is the excitement that surrounded the inception of the school’s humanities program. The innovative interdisciplinary program was born in the 1962-1963 school year, and its success since has long been a source of pride for Ann Arbor schools. Wilkins credits the course with showing him “how everything related to everything else in civilization. The group of teachers who organized it were all very dedicated and creative.” Wilkins’s wife, Jean Gallagher, was also a member of the class of 1963. Today, he and his brother run Perfection Sprinkler on South State, the company his grandfather started in 1932.

Right after graduation, Lyle Salamin moved into management at Arlan’s and worked there until 1970. He’s been working in retail ever since. He used to manage the Kiddie Land on Main and Washington, beneath the old Observer offices, and was able to keep up with all his old classmates who worked downtown. He’s been to most of the reunions, and the memories al-ways come flooding back. “As soon as you walk in you remember everyone,” he says. “You mess up some of the girls’ names ’cause they’re married now and they’ve changed their names, but you re-member them soon enough.”

Blondeen Munson

The class reunions have been mostly pleasant for Blondeen Munson, too, but not entirely. “I had a bad experience at the fifteenth,” she says. “A woman had gone to school with since grade school wouldn’t talk to me.” As a black woman. Munson is more sensitive than most people to the differences between the experiences and memories of white kids and black kids. “I remember the tracking system way back in junior high at Slauson,” she says. “A lot of the black kids were put into the general studies program, and most of the white kids went into the more advanced classes. There was still some segregation in Ann Arbor in those days.”

The class reunions have been mostly pleasant for Blondeen Munson, too, but not entirely. “I had a bad experience at the fifteenth,” she says. “A woman had gone to school with since grade school wouldn’t talk to me.” As a black woman. Munson is more sensitive than most people to the differences between the experiences and memories of white kids and black kids. “I remember the tracking system way back in junior high at Slauson,” she says. “A lot of the black kids were put into the general studies program, and most of the white kids went into the more advanced classes. There was still some segregation in Ann Arbor in those days.”

Most black children in town in the 1950’s went to Jones Elementary School, near the black neighborhoods on North Fourth and Fifth avenues. East Summit, and around the intersection of State and Fuller streets. Munson remembers being one of the few black kids at Mack school. Hers was the second black family on Fetch Street and one of the first to live west of Main. “In junior high at Slauson,” she remembers, “there was only one black kid in the advanced program—Linda Parks, the minister’s daughter.”

It was pretty much the same in high school. Munson says she was fortunate: even though she wasn’t in the advanced program, she was in a section with a lot of kids who were. “Quite a few of the black kids in our class went on to college, even though that’s not how they were tracked,” she says. “I always felt like I had an equal opportunity to do anything.”

Munson, like most of the white members of the class, remembers the dances downtown and after football games at the school. She was, however, the only one to mention that the DI at the downtown dances, Ollie McLaughlin, was black. Munson, too, went to the football games, and remembers that the Ann Arbor High players used to rub the head of Emory Williams, who was black and completely bald, in the huddle for good luck. But Munson doesn’t rattle off stories of late night cruising on the strip. “We used to go to bed pretty early in those days,” she says. “Ten o’clock was late for us.”

Some of Munson’s important memories have nothing to do with race—or even with events within the walls of high school. She remembers being scared during the Cuban missile crisis early in her senior year, when nuclear war seemed a very real possibility, and “the drills where we’d all have to sit under our desks with our hands over our heads, as if that would save us from a nuclear attack. People were building fallout shelters, too. None of my friends’ parents could afford them, but I remember some of the white kids’ parents were building shelters in their backyards.”

She remembers Kennedy coming to the train station in the fall of 1960, just a few months before the election. Nixon stopped there, too, and “we were let out of school for a teacher release day or something so we could all go down and see him. Ann Arbor was a very Republican town then. and I think they wanted a good crowd there for him.”

When Kennedy was elected, Munson says most of the friends she later graduated with were very excited. “Certainly there weren’t any blacks in [his] administration, but it was still a big deal for us. I was preregistering for classes at Eastern Michigan, in Bowen Field House, when I heard that he’d been shot.”

Munson does say she wishes she’d been born a few years later, so she would have reached adulthood farther along in the civil rights movement. Because so many blacks lived in the same few neighborhoods, the black community during her high school years was very tight—so tight, she says, that any black parents would report seeing any black kid skipping school or otherwise misbehaving. But it was also limiting. “I had a few offers to go to black colleges,” Munson remembers, “and I think later on, I would have gone to one of them. I think it would have been good for me to get away. I think I would have ended up a teacher.”

Munson sees lots of old classmates around town now, at lunch breaks from her job at Legal Services near Kerrytown. “I see a lot of people at church, too,” at Bethel AME Church.

Chuck Menefee

Munson remembers her classmate. Chuck Menefee, as “a very, very popular, nice guy, a good athlete who won the state championship in football.” In the 1963 Ann Arbor High yearbook, the Omega. Menefee seems to be mentioned on every other page. High school sports were less specialized then—if you were a good athlete, you were expected to participate every season. But few excelled like Menefee. In his senior year, he was the starting quarterback on the football team and a starting guard on the basketball team, and he had already won two individual state championships in golf. Mention his name to a woman who went to Ann Arbor High around that time and you’ll probably hear him described, succinctly, as a “hunk.”

Munson remembers her classmate. Chuck Menefee, as “a very, very popular, nice guy, a good athlete who won the state championship in football.” In the 1963 Ann Arbor High yearbook, the Omega. Menefee seems to be mentioned on every other page. High school sports were less specialized then—if you were a good athlete, you were expected to participate every season. But few excelled like Menefee. In his senior year, he was the starting quarterback on the football team and a starting guard on the basketball team, and he had already won two individual state championships in golf. Mention his name to a woman who went to Ann Arbor High around that time and you’ll probably hear him described, succinctly, as a “hunk.”

Pioneer High School enjoyed some great athletic successes in the 1980’s, but even they pale in comparison to the glory days of Ann Arbor High in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s. In the fall of 1962, the school had one of its best football teams ever.

Chuck Menefee was the quarterback. His coach, Jay Stielstra, remembers him as “a guy with just amazing leadership abilities. He didn’t have what you’d call a great arm, but he was a great athlete and very smart on the field.” The team’s defense was so strong, Stielstra says. that “we shut out five or six teams that year.” And all year long, the offense lost only three fumbles. Most high school teams lose that many in a single game. The offensive line was so strong, and Menefee such an agile, quick player. that he was never tackled for a loss while attempting to pass.

Ann Arbor High games were major events. Stielstra remembers that when he was a student at the U-M in the late 1950’s, the games were popular even among the college students. Games at the then-new Hollway Field were almost always sellouts, drawing 7,000 or 8,000 fans for a big game like the one against Ypsilanti. “The stands on either side were filled and there were people ringing the end zones,” Stielstra recalls. The next day. “the story of our game was on the front page of the sports section. with at least one picture, usually more.”

The biggest game of the year was Friday, October 12. Ann Arbor was undefeated and ranked number one in the state—the championship then, as in college football today, was determined by a poll of sportswriters—and their opponent. Battle Creek, was ranked number two. In the fourth quarter, with Ann Arbor trailing 14-12, Menefee led the Pioneers down the field. They got a first down near the goal line with twelve seconds left, but they had no timeouts remaining. The safest play would be a dive over the middle by the fullback—but if he were stopped. time would expire before they could run another play.

“I can only remember calling three or four plays that whole season,” Stielstra recalls. “My associate coach, Ed Klum. and I talked it over and sent the play in.” The ball was snapped and Menefee turned to hand off the ball to fullback Kent Leslie, who was immediately tackled by what seemed like the entire Battle Creek team.

But Menefee kept the ball. He looked to the end zone, saw end Ken Dyer all alone, and passed the ball. “Kenny caught it, held on to it for a second, and then threw it about thirty feet in the air,” Stielstra recalls.

Ann Arbor High won the game, 18-14. A few weeks later, after George Perks had coached St. Ambrose past previously unbeaten Detroit Cooley, Ann Arbor High was named the state football champion. Menefee was named first team allstate. They were heady days.

All Menefee says now about his fabled high school years is that he “stayed pretty active.” The player on the receiving end of the big play, Ken Dyer, played for Arizona State and then in the NFL for the Cincinnati Bengals. But at five feet nine, Menefee lacked the size to be a bigtime college quarterback. A few smaller schools came calling in his senior year, Stielstra says, but he wasn’t what you’d call a “bluechipper.”

Menefee went to Michigan State, got his degree in economics, and worked as a stockbroker for a few years. “It took me a while to figure out what I wanted to do,” he says. Later, he went back to Michigan State and picked up a degree in agronomy, the science of crop production and soil management. Always an avid and talented golfer—one classmate recalls him winning club tournaments at Barton Hills when he was in junior high—Menefee became involved in golf course management.

He worked at the U-M’s Radrick Farms course for a few years and now manages a course up north that he designed and helped build. The Little Traverse Bay Golf Club, which Menefee modestly describes as an awesome course,” has been named one of the best new courses in the country by several publications.

Menefee still sees a lot of Ann Arbor High friends when he gets back to town. Other classmates call him or stop by for a round when they’re up north golfing or skiing. And his assistant at Little Traverse Bay is Howie Lippert—the starting quarterback for Ann Arbor High in 1960.

Peter Dodge

Peter Dodge’s football memory, of the stabbing at the game and the law and order panic that ensued, is atypical—no other member of the class of ’63 even mentioned it. Oliver Stone may be right that the 1960’s didn’t really begin until November of 1963, when President Kennedy was killed. Sandi Coleman says her class was far more influenced by the 1950’s—at least until they graduated and moved into the real world.

Peter Dodge’s football memory, of the stabbing at the game and the law and order panic that ensued, is atypical—no other member of the class of ’63 even mentioned it. Oliver Stone may be right that the 1960’s didn’t really begin until November of 1963, when President Kennedy was killed. Sandi Coleman says her class was far more influenced by the 1950’s—at least until they graduated and moved into the real world.

The class of ’63 went to high school in an innocent time. Vietnam was still a few years away from the nation’s consciousness, local racial tensions were not that high, and the economy was in the midst of the longest sustained boom on record. The world was divided clearly between the bad guys, the communists, and the good guys, us.

So the class can be forgiven for not being all that interested in social causes. But the stabbing was different. It threatened to affect them directly, as nothing so far had. “It was in September or October of our senior year,” Dodge remembers. “Nothing like that had ever happened at a football game before. There had been some fisticuffs, but that was about it.”

Soon after, the city council began discussing the idea of enforcing a citywide curfew for kids under eighteen. The incident had shocked the community, and the community wanted to respond. “The city wanted input from students,” Dodge remembers, “and as one of the kids on student council, I was part of the group that met with city council. We were able to convince them that we as a student body were taking the matter very seriously, that we were concerned by it, but that we were interested in seeing that it didn’t happen again.

“I think they were impressed by that. Now this was before student demonstrations at colleges, and before student rights and all that. The city council was just impressed by how we were dealing with it and they said. ‘All right, no curfew.’ I was very proud of that. I have very positive feelings about how we were dedicated to a productive environment in our school.”

Aside from that incident, Dodge remembers high school as a quiet time. “Race relations, or racial tensions, was not a subject that was addressed,” he says, though he, too, remembers that most blacks were tracked into general studies.

After high school, the issues got bigger and he became more aware. “In the summer of 1963,” Dodge recalls, “the local Congress of Racial Equality began actively pursuing a fair housing act to end discrimination. It was unlike anything Ann Arbor had seen before. I remember walking past City Hall and seeing the pickets and realizing, when I thought about it, that they were right. Ann Arbor was a segregated community and integration was necessary. I got involved.”

His involvement continues to this day. After college at Amherst, a year working with VISTA in Appalachia, and a tour in the service during the Vietnam War—he says he enlisted because it seemed like the right thing to do—Dodge went to the U-M law school. Here in town, his billable hours as an attorney (his office is on East Liberty) are spent mostly on real estate and probate cases. But he also represents the Shelter Association of Ann Arbor pro bono and works there as a volunteer. His classmate Blondeen Munson calls him “a great attorney who does some very nice things for people.”

Dodge’s two children graduated from Pioneer High School; while their experiences there were good, he thinks his was a more fortunate time. “When we graduated in 1963,” he says, “the opportunities seemed unlimited. There was no war, the economy was strong, and there was a great demand for people with college educations. Now, even people with college degrees have a hard time.

“I think kids now expect less of the world than we did. We thought we were going to change the world.”

Cindy Wild

Unlike the lives of many of her classmates, Cindy Helber’s life has stayed true to her expectations. In her senior year, when she was Cindy Wild, she was the captain of the cheerleading team. She was also engaged. “I was engaged in my junior year,” she says. “The guy I was dating was older. He was in college. We got engaged when I was a junior and got married right after I graduated.” Cindy and Bob Helber have been married nearly thirty years.

Unlike the lives of many of her classmates, Cindy Helber’s life has stayed true to her expectations. In her senior year, when she was Cindy Wild, she was the captain of the cheerleading team. She was also engaged. “I was engaged in my junior year,” she says. “The guy I was dating was older. He was in college. We got engaged when I was a junior and got married right after I graduated.” Cindy and Bob Helber have been married nearly thirty years.

She has worked over the years, but not at anything she’d call a career. “I worked to put my husband through college, and then when it was time for me to go to college, I got pregnant,” she says without much regret. She’s been a fulltime mom and wife ever since. “Coming out of high school,” she remembers. “I thought I was going to get married, have kids, and live happily ever after. That’s just what I’ve done.”

Her high school years, Helber say were “some of the best years” of her life. So when her own son and daughter went to Pioneer, she was dismayed at some of the things they encountered there. The biggest difference between what they went through and what I did,” she ‘says, “is the prevalence of drugs and the openness of sex today.” She says her nephew told her that it wasn’t uncommon for kids today to use cocaine at high school parties—a far cry from the “grassers” she remembers from 1963, so named because they sat on the lawn outside the house where the party was and drank beer.

And she’s amazed at the difference in attitudes toward sex. In her day, she says, “you knew who the girls were who were promiscuous and you thought of them as sluts.” Judging from the stories her daughter told her about the sexual exploits of her classmates, Helber says, “today, it seems like everyone’s promiscuous.”

Birth control pills were introduced in 1960; by 1963, they hadn’t made their way into high schools, and abortion was illegal. The consequences of fooling around could be pretty permanent—”till death do us part.” Helber remembers one girl who became pregnant in high school and had to finish her studies at home. There were also secret scares that weren’t all that secret. If somebody was pregnant, or thought they were, everyone talked about it,” she says.

Bob Seger

Some of the expectations of the class of ’63 were unmet. “In high school,” Dodge says, “I don’t ever recall even hearing of Vietnam. The service then was just another option, something else to do be-sides going to college or getting a job. The likelihood of people being drafted was not even considered.”

Some of the expectations of the class of ’63 were unmet. “In high school,” Dodge says, “I don’t ever recall even hearing of Vietnam. The service then was just another option, something else to do be-sides going to college or getting a job. The likelihood of people being drafted was not even considered.”

Within just a few years, “student deferment” had become everyday parlance. By December 1967, there were 475,000 American troops in South Vietnam. Among those hundreds of thousands was Neil Stehle of the class of 1963.

When word got out of Stehle’s death, it sent shock waves through the class. He wasn’t the only class member killed in Vietnam—George Airey, son of the builder responsible for several subdivisions near the high school, also was killed there—but he had been among the highprofile people, a member of the “in” crowd. “Neil was a pretty popular kid,” says Larry Hahn. “He was probably the best known of the kids from school that died over there.”

What made it the most troubling, of course, was that it could have been any of them. Except for a student deferment, a preemptive enlistment in the National Guard, or a physical flaw, they could have been there. Those who were there knew exactly how random death was.

On May 24, 1963, just a few weeks before graduation, the class had received an earlier lesson in that subject. On Coilingwood Avenue in Toledo, at 2:30 a.m., a station wagon carrying three Ann Arbor High seniors spun out of control. It skidded for 408 feet and crashed into a steel utility pole. One of the students, Don Jedele, the son of the city controller, was killed. The driver, Chuck Keen, survived. So did their friend, who was sitting between them in the front seat Bob Seger.

The public memorial service for Jedele, Lyle Salamin says, “was the biggest one I’ve ever been to, that’s for sure. They had it at ArborCrest on Glacier Way, and we were all let out of school. There must have been a couple thousand people there.”

The class of ’63 could have lost its most famous product that night. Bob Seger was already playing at clubs and dances back then. In the 1963 Omega, on the page describing the senior talent show, several acts are listed before a mention that “Other performers were Bob Seger and his combo consisting of Pete Stanger, Chuck Keen and Tom Rolston.”

“Bobby was a big part of the gang 1 ran with,” says Lyle Salamin. “He used to play at just about any bar in town—the Schwabeh, the Dandy Lion in South Lyon—plus the fraternities and dances. He was hardly ever around ’cause he was playing with his band somewhere almost every night. I remember one time the hot rod club I was president of—the Ann Arbor Road Aceswe were having a party and I got Bobby and his band to play there. We couldn’t get anybody to come ’cause they were so sick of seeing him everywhere.

“He really worked hard. He deserves everything he’s got.”

What Seger has is sixteen albums, from “Ramblin’ Gamblin’ Man” (1968) to his most recent, “The Fire Inside” (1991). Seger didn’t break through nationally until “Night-Moves” in 1976. But by now, even the most casual music fans have been exposed to his music. Tom Cruise danced in his underwear to Seger’s “Old Time Rock and Roll” in “Risky Business,” and “Like a Rock” is the most memorable part of the GM truck commercials that are played with alarming regularity during televised sports events.

Seger has not formally taken part in any of his class’s reunions, but he did drop in on a party before the twentyfifth. He made quite an impression. “I think he was in the middle of a separation from his wife,” remembers a classmate. “He ended up having quite a bit to drink and getting kind of obnoxious.” Explains another schoolmate, “I think Bobby is still in a rock and roll, entertainment mode, where the rest of us are settling down a bit.” It’s unlikely that Seger will make it to this year’s reunion. He’s getting married, again, that weekend.

Ron Westrum

Ron Westrum, a member of the class who’s now a sociology professor at EMU, echoes many of his classmates in characterizing their high school years. “It was the beginning of the end of the age of innocence,” he says. “The Sixties had only just begun. Black and white liberals got along together pretty well. Our high school was really a marketplace for ideas. I think a lot of us were pretty naive. It looked like the world was going to be more integrated. Atomic power was not yet a great evil.

Ron Westrum, a member of the class who’s now a sociology professor at EMU, echoes many of his classmates in characterizing their high school years. “It was the beginning of the end of the age of innocence,” he says. “The Sixties had only just begun. Black and white liberals got along together pretty well. Our high school was really a marketplace for ideas. I think a lot of us were pretty naive. It looked like the world was going to be more integrated. Atomic power was not yet a great evil.

“Then the Sixties totally changed people’s attitudes. When I went off to college, people asked me if I was going to do drugs and I said, ‘Sure, why not?’ People’s attitudes about technology changed. With the war and napalm, science became bad. The lid just came off the box—free love, drugs, free sex.”

Compared to the closeness of his own high school class thirty years ago, one member of the class of ’63 says, “Nowadays, it seems like you have a group of kids that play baseball, and they hang around together. Then you have the music kids or the drama kids. That’s all they do, and those are the people they talk to.”

Ron Westrum agrees with that assessment. “There doesn’t seem to be as much of a sense of community today. For instance, when I was going to school, I don’t think we could imagine that a magazine called Self would be very popular.”

“We were the end of an era,” Blondeen Munson says evenly. “We were the last class before the baby boom really peaked, the last class of the Fifties, the last real Cold War kids. It seems like a very long time ago.”